Entrevista con Isaac Stewart (1 de 3) – Cartografiando mundos de fantasía

Prólogo: Saber dónde estás, por Ysondra

Cuando era pequeña, me encantaba la historia, especialmente la historia antigua sobre los griegos, el Imperio Romano y Egipto. También me sentía muy atraída por Asia Oriental, pero por otro lado, odiaba la geografía. Quizás porque tenía que aprenderla de memoria, y mi padre solía ayudarme a memorizar, y no podía ver mis series favoritas hasta haber recitado de memoria cada detalle geográfico sobre un mapa. Lo odiaba. Pero la historia… Eso era algo completamente diferente. Era como leer un viejo libro de aventuras.

Mi recuerdo más querido sobre la geografía se remonta a uno de cuando yo tenía unos siete años. Acabábamos de descubrir los mapamundis en clase. Así que la profesora nos dividió en grupos, y nos repartió algunos mapamundis para jugar y descubrir nuevos lugares. Así que, bien, la primera cosa que quería saber dónde se encontraba era Nueva York, porque Spiderman vivía allí, y también vivían allí los X Men en la Mansión X. Y después, Massachusetts, porque allí se encontraba la academia del Club Fuego Infernal. Y después de eso, tenía todo el sentido del mundo buscar Metrópolis y Gotham, porque si Massachusetts y Nueva York estaban en el mapa, esas dos otras ciudades debían estar también. Así que, aquí venía la pobre profesora, a preguntar qué estábamos haciendo, tan centrados como lo estábamos en el mapa. Y fue entonces cuando le dije que estábamos buscando Gotham y Metrópolis… Se quedó sin palabras durante un rato…

Cuando me hice mayor, y ya estaba trabajando, empecé la carrera de Estudios de Asia Oriental, en la UOC (que es una universidad a distancia para quienes no tienen tiempo de asistir a clase en persona). Es algo que espero poder retomar algún día. Estaba leyendo sobre la fundación de China, y me lo estaba pasando muy bien pasando las páginas desde el punto donde me encontraba, hasta los mapas situados al final del libro. Estaba encandilaba con los ríos Yangtze y Huang He, y realmente disfrutaba ubicando en el pequeño mapa las ciudades y eventos sobre los que estaba leyendo.

Y ese día, tuve una epifanía. No puedes aprender, ni entender, historia sin la geografía. Y digo más, empecé a darme cuenta de que una de las cosas que adoro por encima de todo en un libro de fantasía son… Los mapas. No hay buena novela de literatura fantástica sin un mapa donde ubicar qué está pasando dónde… ¿Quién podría entender Canción de Hielo y Fuego sin un mapa de Westeros? ¿Quién podría seguir la acción dentro de Las Crónicas de Malaz sin los mapas? Nadie. O, puedo recordar otro momento embarazoso, cuando me di cuenta de que sabía más de Azeroth que de la propia Europa. Básicamente, porque había pasado muchísimo tiempo viajando por Azeroth.

Así que me di cuenta de lo tonta que fui de pequeña, y odiaba la geografía. O quizás, no me inculcaron amar la geografía de verdad, porque no había nadie que supiera cómo enseñarme a apreciarla. La geografía es una herramienta primordial para entender nuestro mundo, y cualquier mundo que visitemos con nuestras mentes. Nos ayuda a entender su evolución. Y no hay mejor forma de aprender, que viajando. Físicamente… O con nuestra imaginación.

Así que, digamos que la literatura fantástica me enseñó a entender su importancia.

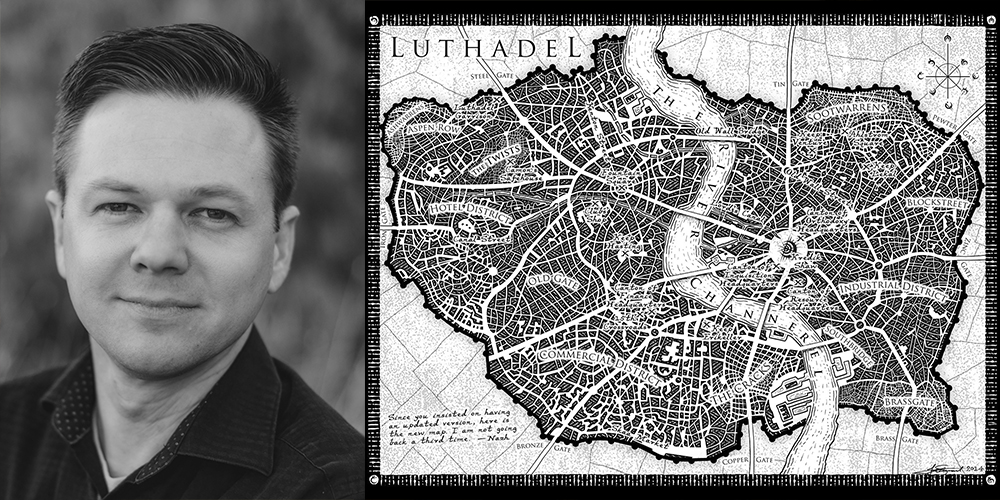

Y hoy, tenemos el privilegio de hablar con un artista que nos acompaña y nos da la bienvenida en esos universos. Su nombre es Isaac Stewart. Le conoceréis por sus impresionantes mapas y por su arte en los libros de Brandon Sanderson… Pero hay mucho más que descubrir sobre él.

Estamos muy emocionados por esta entrevista, que de alguna manera se nos ha ido un poco de las manos… Y tendremos que publicarla en tres partes. Esta semana, Isaac nos hablará un poco sobre él, sobre cómo crear mapas para mundos de fantasía, y cómo acabó trabajando con Brandon.

Prologue: To know where you are, by Ysondra

When I was a child, I really loved History, specially ancient History about Greeks, the Roman Empire and Egypt. I also was kind of mystified by Eastern Asia, but then, somehow I hated Geography. Maybe because I had to learn it by heart and my dad used to help me memoryze, and I wouldn’t be able to watch my favourite TV series until I spoke out loud each and every geographical detail on a map. I do hated that. But History… That was something different completely. It was like reading an old story.

My most beloved memory on Geography is one from when I was around 7 years old. We just discovered the world map in class. So the teacher made some groups with us, gave us some world maps to play with and discover different places. So OK, first thing I wanted to find where it was, was New York, because Spiderman was living there and so were the X Men within the X-Mansion. And secondly Massachusetts, because there was Hellfire Club’s Academy. So after that, it totally made sense to search for Metropolis and Gotham, because if Massachusetts and New York where on the map, those other two cities should be as well. So here it comes the poor teacher, to ask what were we up to, since we were totally focused on the map. And that was when I told her we were looking for Gotham and Metropolis… She was speechless for a while…

When I grew up and I was already working, I started Eastern Asia Studies, at UOC University (which is an online University for those who haven’t the time to attend in person). That’s something I hope I will go back one day. I was reading about China’s foundation, and I was having a really nice time going back and forth from my current page to the maps on the rear of the book. I was mesmerized about Yangtze and Huang He rivers, and really enjoyed allocating the cities and events I was reading about, on the tiny map.

And that day I had an epiphany. You cannot learn, nor understand History without Geography. And furthermore, I started to realize that one of the things I loved the most from a fantasy book were… The maps. There is no good fantasy novel without a map to see what’s going on where… Who would understand A Song of Fire and Ice without Westeros’ map? Who might be able to follow the action within Malazan Book of the Fallen without the maps? No one. Or I can recall another awkward moment, when I realized I knew more about Azeroth than about Europe itself. Mainly because I expended a lot of time travelling around Azeroth.

So I realize how silly I was when I was a child, and hated Geography. Or maybe, I wasn’t taught properly to love Geography, because no one really knew how to teach me how to appreciate it. Geography is the primary tool to understand our world, and whatever world we are visiting with our minds. It help us understand its evolution. And there is no better way to learn it, than travelling. Physically… Or with our imagination.

So let’s say, fantasy books helped me understand how important that is.

And today, we have the privilege to talk to one of the artist who walks us and welcome us in those universes. His name is Isaac Stewart. You will know him by his awesome maps and art for Brandon Sanderson’s books… But there’s much more to discover about him. We were so excited about this interview, that somehow this got a bit out of hand… And we will splitting the interview in a three part series.

Entrevista con Isaac Stewart (1 de 3): Cartografiando mundos de fantasía

Interview with Isaac Stewart (1 of 3): Creating maps for fantasy worlds

C: Muchas gracias, Isaac, por compartir tu tiempo con nosotros. Estamos muy contentos por hablar un poquito contigo, y lo apreciamos mucho, especialmente sabiendo todos los proyectos en los que te encuentras inmerso, no solo en relación a los libros de Brandon, si no también con Grim Oak Press, y Tad Williams.

Muchos de nuestros amigos lectores quizás te conozcan por los hermosos acentos al principio de los capítulos y los mapas que has estado creando, pero hemos oído que también tienes un pasado como artista 3D, contribuyendo en la industria de los videojuegos, y que también tienes planes para una máquina-que-viaje-más-rápido-que-la-luz. Nos encantaría saber un poco más de ti.

IS: ¡Hola! Estoy muy emocionado por hablar con todos vosotros hoy. Sí, solía trabajar como artista 3D en la industria de los videojuegos. Antes y durante la facultad, ayudé a crear juegos educativos, vídeos musicales, y libros de lectura sencilla para enseñar a los niños a leer y los números. Y después de eso trabajé en A Kingdom for Keflings, Twisted Metal para PS3, y Disney Infinity, entre otras cosas. Si pasas mucho tiempo en la industria de los video juegos, trabajas en muchos proyectos, y una gran parte de ellos son lanzados jamás.

Entre la compañía de juegos educativos y trabajar en videojuegos propiamente dichos, retomé los estudios como graduado pensando que iba a ser un optometrista. Tomé una clase de escritura, conocí a Brandon Sanderson justo antes de que Elantris fuera publicada, y empecé a hacer mapas para él, comenzando por Nacidos de la Bruma. Para pagar las facturas durante aquella época, trabajé como diseñador gráfico en una empresa de boquillas para gasolina, y también trabajé los viernes y sábados por la noche en la recepción de un hotel.

Mapa para NES de La leyenda de Zelda

C: ¿Cómo nace un cartógrafo de mundos fantásticos? ¿Era una afición previa? Por ejemplo, los que nos gusta jugar a rol, a veces necesitamos dibujar los mapas para nuestras propias campañas. O a veces quieres explicar una historia, y de alguna manera quieres dar forma el mundo y enseñárselo a otras personas de forma comprensible… ¿Cuándo empezaste a crear mapas? ¿Recuerdas el primero?

IS: Mi recuerdo más temprano sobre los mapas es de aquel viejo globo terráqueo que tenían mis padres. Lo hacía girar para ver dónde caía mi dedo. La simple idea de que existiera un lugar de la tierra que estuviera representado en el mapa, me fascinaba. Cuando Nintendo lanzó La Leyenda de Zelda para la NES, hice un mapa de Hyrule utilizando lápices de colores sobre un par de piezas de papel cuadriculado que pegué utilizando cinta adhesiva. Papá tenía aquellos viejos libros de bolsillo del Señor de los Anillos, y recuerdo encontrar los mapas en su interior y pensar, “¡Guau! ¡Parecen tan reales, pero este sitio solo existe en las mentes de las personas que leen el libro!” No leería los libros hasta tener 14 o 15 años, pero de joven ya era un fan tan solo por los mapas.

En una clase de lectura de sexto de primaria, leímos El Hobbit, y para un proyecto, tuvimos que crear nuestro propio mapa de fantasía y escribir tres capítulos de una historia. ¡Eso encendió mi imaginación! Todavía puedo ver en mi cabeza el mapa que cree, y los personajes que dibujé para acompañar el mapa. Ojalá pudiera recordar el nombre de esa profesora, porque le debo muchísimo por abrir mi mente a la fantasía.

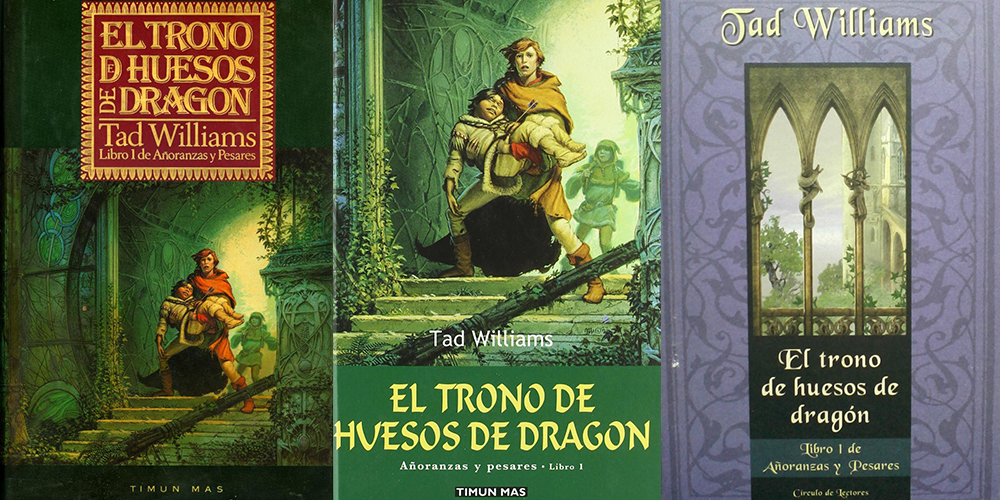

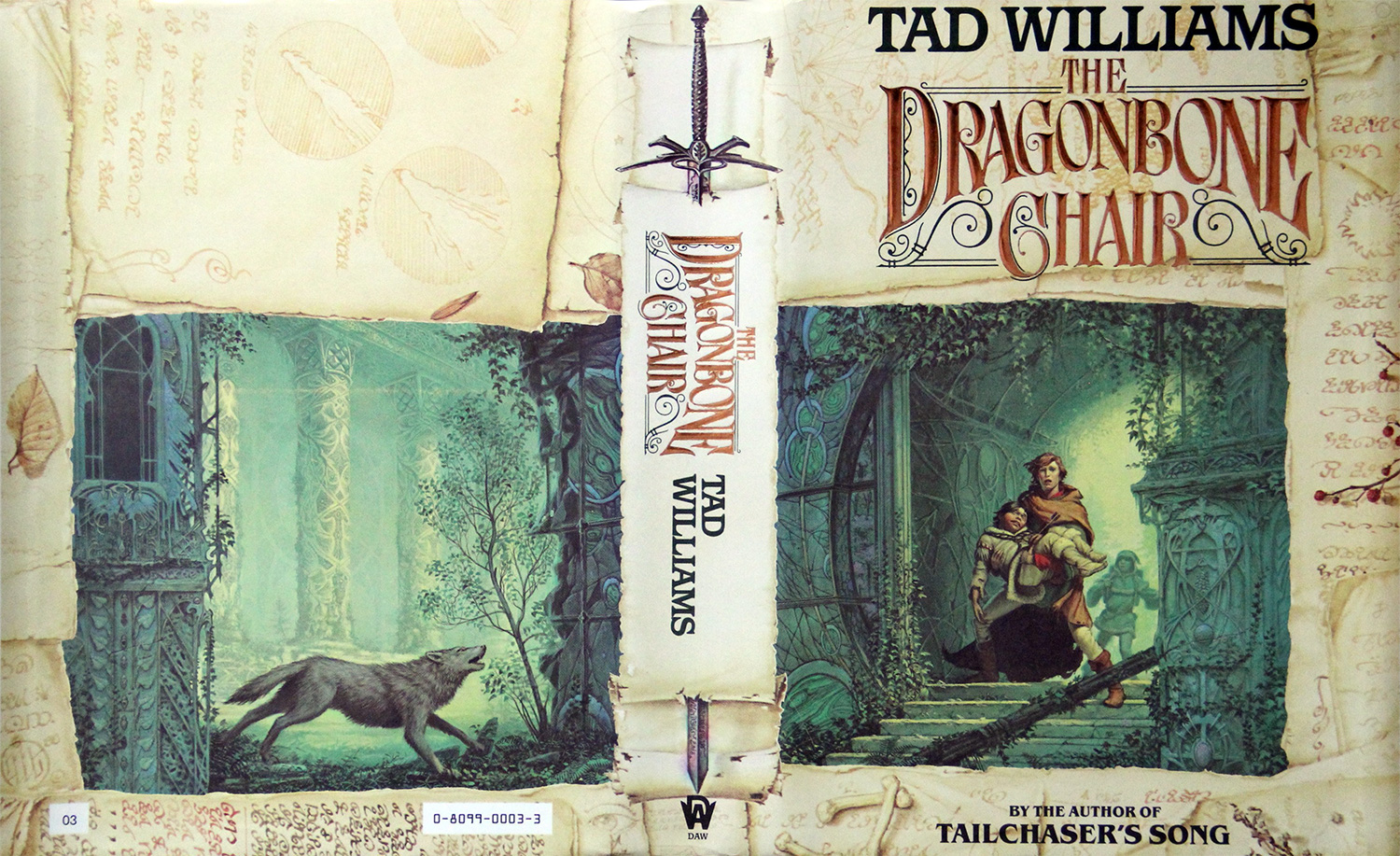

Pasaron otros dos años, a pesar de todo, antes de que encontrara el libro que realmente me atrapó en la lectura de literatura fantástica. Mi tía le envió un paquete a mi padre por su cumpleaños, y siendo un adolescente que no conocía los límites de la propiedad privada, abrí el paquete antes de que él llegara a casa. Era una edición de bolsillo del libro de fantasía épica que por aquel entonces acababa de ser publicado, El Trono de Huesos de Dragón, de Tad Williams. Lo leí, y me enganché a la literatura fantástica. Me encontré a mí mismo intentando escribir historias y crear mapas para mis propios mundos. Rebuscaría entre antiguos diccionarios para encontrar nombres para los emplazamientos. Incluso cree un sistema solar entero y nombré algunos de los planetas en honor a la chica de la que estaba enamorado en el instituto (N.T.: Lo siento mucho, pero tengo que decirlo: <3 Ooooooooooooooooh <3). Encontré un grupo de escritura en Genie, llamado Fantasy School, y lo siguiente fue crear mapas para el mundo compartido que estábamos concibiendo allí.

Soy un minimalista, por lo que desgraciadamente, no conservo ninguno de mis primeros mapas.

Ediciones españolas de El Trono de Huesos de Dragón, de Tad Williams.

C: ¿Cómo es el proceso creativo de dar vida a un mapa?

He descrito parte del proceso detalladamente en Tor.com, en este link (N.T.: hemos traducido el artículo para que podáis leerlo en castellano, siguiendo el link). Pero estoy contento de poder desarrollar un poco el tema aquí.

En primer lugar, siempre estoy aprendiendo. A veces, verdaderos expertos sobre mapas señalan defectos en mis mapas, y he podido aprender de ello, por lo que lo que diga a continuación puede no ser lo mismo que piense sobre el proceso dentro de unos años.

Estoy convencido de que hay cosas que hago de forma inconsciente cuando me enfrento a un nuevo mapa, pero estas son las tres cosas que frecuentemente tengo en mi cabeza cuando creo mapas: claridad, estilo, y escala. Si le preguntaras a alguien que realizaba mapas reales durante el Renacimiento, sus respuestas variarían en función del propósito del mapa. Si le preguntas a los cartógrafos de hoy en día, probablemente también obtendrías respuestas distintas.

Dado que mis mapas se utilizan mayormente como algo para aclarar el texto de una novela, mi principal propósito es la claridad. La claridad se sobrepone tanto sobre estilo como sobre la escala. El mapa necesita ser útil para quienes están leyendo el libro. Uno no debería tener que buscar demasiado para encontrar lo que están buscando, antes de retomar la lectura. Si creara un mapa destinado a ser un poster, me preocuparía menos por la claridad, ya que el propósito del mapa es ser contemplado y disfrutado ante todo como una pieza de arte, pero cuando tan solo tienes quince por veintitrés centímetros, los lectores solo pueden aguantar fuentes pequeñas y nombres kilométricos hasta cierto punto.

Antes de empezar un mapa, intento hacerme una idea del estilo. Muchas veces me inspiro en mapas que he visto en museos, en internet o en colecciones privadas. ¿Qué es lo que encaja con la cultura que ha creado el mapa? ¿Utilizarían las herramientas y técnicas que estoy emulando conforme doy vida al mapa? ¿Quién está creando este mapa? ¿Y para quién? Se parece un poco al método en interpretación. Te adentras en la historia del mapa. De pequeño, hacía mapas piratas, y después les quemaba los bordes. En lo que pienso ahora, que en aquel entonces no pensaba, es esto: ¿cuál es la historia tras las quemaduras del mapa? ¿Por qué está manchado aquí? ¿Porqué tiene esas marcas de dobleces?

La escala es importante, especialmente si el autor/cliente quiere ser capaz de utilizar el mapa para comprobar las distancias de forma fidedigna en sus mundos. Así que siempre busco pistas en el texto que me indiquen las distancias y el tiempo que se tarda en viajar de un punto a otro. El estilo prima sobre la precisión de la escala. No me preocupa que alguien pueda colocar un sextante y pueda utilizar mi mapa para navegar a alguna tierra de fantasía. Existen precedentes a esto: algunos mapas antiguos tenían un estilo genial, pero no eran realmente precisos. Loa mapas de la antigüedad a menudo eran creados por personas que no habían estado en los lugares que estaban describiendo. No conocían las distancias entre Alejandría y Constantinopla, pero sabían gracias a los marineros que había varias ciudades entre ambos destinos. Así que separaban equitativamente el espacio de los puertos entre las dos ciudades en el mapa. Eso no implicaba que hubiera la misma distancia entre puertos, pero como marinero, por lo menos podías saber qué puerto iría a continuación, y cuántos puertos había entre ubicaciones.

Así que la idea de crear un mapa formidable con un estilo distintivo suele estar presente en mi cabeza por encima incluso de la claridad, pero al final, la claridad gana sobre el estilo, y el estilo suele ganar a la escala.

Conforme trabajo en el mapa, a menudo consulto geografía del mundo real. Como joven cartógrafo cometí errores que no habría cometido de haber sabido más geología y geografía, y estoy convencido de que existen fallos que estaré cometiendo ahora mismo porque todavía no he aprendido a hacerlo mejor. Investigar mapas reales, y la historia geográfica de emplazamientos reales me ayuda a darme cuenta de dónde tienen una carencia mis habilidades. No tienes que saber toda la geología de tu mundo ficticio antes de realizar mapas. Por lo general colocas una cadena de montañas donde queda bien y más tarde te planteas los motivos por los que esa cordillera está ahí, pero no está de más saber, por ejemplo, en qué lugares es más probable que aparezcan las montañas dentro de una masa terrestre. También puedes fijarte en las células de Hadley para los desiertos, y en los vientos alisios y los vientos del oeste para ver los patrones macro del viento y las localizaciones desérticas. Imagínate El Niño y La Niña. Pero no te quedes atascado en los detalles.

Cuando me quedo encallado, o cuando estoy buscando un mapa de referencia, existen algunos lugares que me gusta visitar. A veces merodeo por una web llamada cartographersguild.com y me fijo en los trucos y consejos de los cartógrafos que están haciendo algunos de los mejores mapas que he visto jamás. Reviso a menudo DeviantArt y blogs de artistas, y me fijo en cómo realizan sus trazos o el color de sus piezas. Frecuentemente suelo fijarme en cartógrafos de todo el mundo durante todos los períodos de la historia, mirando qué hicieron. Hace poco visité una colección de mapas privada y hablé con el conservador sobre los tipos de papel y tintas que se emplearon en mapas específicos. Aquella visita todavía me maravilla y cambia la forma en la me enfrento a crear mapas que parezca que provienen de períodos históricos reales.

A menudo se me acercan nuevos cartógrafos de fantasía para preguntarme cómo empezar. Aquí dejo unas pocas ideas.

Aprende todo lo que puedas de cartografía, geología y geografía, pero no dejes que tu investigación interfiera en el camino de crear tus propios mapas. Será en el proceso de creación en el que caerás en los problemas cuyas respuestas (cuando las descubras) harán de ti un mejor cartógrafo.

Hace unos pocos años realicé una presentación en una convención sobre los siete pecados capitales de la cartografía fantástica. Estoy convencido de que hay muchos más que siete, pero la lista es un buen punto de partida a la hora de averiguar qué hacer y que no hacer en nuestros propios mapas.

Advertencia: a veces, un autor os pedirá que hagáis el mapa de una cierta manera, a pesar de estos errores. Hay varios mapas míos por ahí que contienen los mismos errores que estoy a punto de describir. En ocasiones el autor me ha pedido que mantuviera las cosas tal cual, en otras ocasiones he cometido los errores yo solo. La cosa aquí es la siguiente: incluso si caes en el error, no es el fin del mundo. Siempre puedes quitarle hierro al error diciendo algo como: “¡Pero el cartógrafo de ese mundo que realizó el mapa no sabía que había un río ahí!”

Los Siete Pecados Capitales de la Cartografía Fantástica

- Un mapa sin propósito. ¿Quién ha creado este mapa? ¿Quién lo ha encargado? ¿Por qué? Esto puede ser algo tan sencillo como: “Soy un escritor de literatura fantástica y necesito saber dónde está todo, para poder escribir mi apestoso libro.” Puedes romper alguna de las reglas si ello sirve al propósito del mapa.

- Involuntariamente, no existe escala.

- Montañas o formaciones de tierra que no siguen las leyes naturales. Por ejemplo, una masa de tierra que se asemeja de manera demasiado perfecta a un dragón (¡a mí me ha pasado!), o una cordillera de montañas que forman una línea perfecta de norte a sur (a menos de que este sea el estilo intencionado en el mapa), pero las montañas no se forman de manera natural en líneas perfectas.

- Ríos que fluyen hacia la montaña.

- Climas y biomas ubicados de forma que no se darían en la realidad (junto a esto están los planetas que son un único bioma. George Lucas se escapó de esta, pero eso no quiere decir que sea fiel a la realidad.)

- Colocar pueblos y ciudades donde no tiene sentido lógico (por ejemplo, que no tengan cerca una fuente fresca de agua.)

- Los límites no son fieles a su período temporal. Las fronteras nacionales representadas por líneas rectas son algo relativamente nuevo. Fíjate en las fronteras de los estados durante el Sagrado Imperio Romano. Parecían piezas de un puzzle.

C: Thank you very much, Isaac, for sharing your time with us. We are really excited to talk to you a bit, and we do appreciate it, specially knowing all the projects you are currently involved in, not just regarding Brandon’s books, but also with Grim Oak Press, and Tad Williams.

Most of our fellow readers may know you thanks to the beautiful accents, art, and maps you have been creating; but we heard you have also a history as 3D artist, contributing within the videogame industry, and also that you have plans about a faster-than-light travelling machine. We would love to know a bit more about yourself.

IS: Hi! I’m excited to talk to you all today. Yes, I used to work as a 3D artist in the videogame industry. During and after college, I helped create educational games, music videos, and easy-reader books for teaching kids numbers and how to read. Afterward I worked on A Kingdom for Keflings, Twisted Metal for the PS3, and Disney Infinity, among other things. If you spend much time in the video game industry, you work on a lot of projects, and a good portion of them are never released.

Between the education game company and working in straight-up video games, I went back to school as a post-grad student thinking I was going to be a optometrist. I took a writing class, met Brandon Sanderson right before Elantris was published, and started doing maps for him beginning with Mistborn. To pay the bills during that time, I worked as a graphic designer at a gasoline nozzle company and also worked nights on Fridays and Saturdays at the front desk at a hotel.

Legend Of Zelda Map Nes

C: How is a fantasy cartographer born? Was it a previous hobby? For example, the ones of us who love to roleplay, sometimes are in the need to draw our own campaign’s map. Or sometimes you are willing to tell a story, and somehow want to shape the world and show it to others in a comprehensive way… When did you started to create maps? Do you remember your first?

IS: My earliest memory of maps is an old globe my parents had. I’d spin the thing and see where my finger would land. The whole idea that there was a place on earth that was represented on the map fascinated me. When Nintendo released The Legend of Zelda on the NES, I mapped Hyrule using colored pencils on a couple of pieces of graph paper taped together. In addition, Dad had these old paperbacks of the Lord of the Rings, and I remember finding the maps in there and thinking, “Wow! These look so real, but this is a place that exists only in the minds of the people who read the book!” I wouldn’t read the books till I was 14 or 15, but I was a fan already at a young age because of the maps.

In 6th grade reading class, we read The Hobbit and, for a project, had to create our own fantasy map and write three chapters of a story. This ignited my creativity. I still can see the map in my head that I created and the characters I drew to go with the map. I wish I could remember that reading teacher’s name, because I owe a lot to her opening my mind to fantasy.

It was another two years, though, before I found the book that really got me into reading fantasy. My aunt sent a package to my dad for his birthday, and I being a teenager and not knowing the boundaries of propriety, opened the package before he got home. It was a paperback of the then just-released epic fantasy The Dragonbone Chair by Tad Williams. I read it and was hooked. I found myself trying to write stories and create maps of my own worlds. I’d dig through old language dictionaries to find names for the places. I even created a whole solar system and named some of the planets after my junior high crush. I found a writing group on Genie called Fantasy School, and next thing I was creating maps for the shared world we were creating there.

I’m a minimalist at heart, so unfortunately, I no longer have any of my earliest maps.

The Dragonbone Chair, by Tad Williams. Daw Publishers Cover.

C: How is the creative process to bring a map to life?

IS: I’ve detailed some of the process on Tor.com at this link. But I’m happy to elaborate a bit here.

First off, I’m continually learning. Occasionally, true map experts have pointed out flaws in my maps, and I’ve been able to learn from that, so what I say here might not be exactly my feelings or process a few years from now.

I’m sure there are things I’m unconsciously doing as I approach a new map, but these three things are often on my mind: Clarity, style, and scale. If you were to ask someone creating real maps back in the Renaissance, their answers would be different depending on the purpose of the map. If you ask other mapmakers today, you’d probably get various different answers, too.

Since my maps are mostly used as something to elucidate the text of a novel, my main purpose is Clarity. Clarity trumps both style and scale. The map needs to be usable to those reading the book. One shouldn’t have to search too much to find what they’re looking for before they dive back into reading. If I create a map meant to be presented as a poster, I worry less about clarity because the map is meant to be viewed and enjoyed as a piece of art first, but when you only have six inches by nine inches, readers can only tolerate small font sizes and endless names up to a certain point.

Before starting a map, I also try to find the style. Oftentimes I’m basing it on maps I’ve seen at museums, on the internet, or in private collections. What fits with the culture who produced the map? Would they use the tools and techniques I’m simulating as I create the map? Who is creating this map? And for whom? It’s a bit like method acting. You’ve get inside the map’s history. As a kid, I’d make pirate maps and then burn the edges. What I think about now that I didn’t think about then is this: what is the story behind the map having the burns? Why is this stain here? Why are these fold marks there?

Scale is important, especially if the author/client wants to be able to use the map to judge distances accurately in their world. So I’m always looking for hints in the text that tell me about distances and time it takes to travel from one point to another. Style trumps accuracy in scale. I’m not worried about someone being able to pull out their sextant and use my map to sail to some fantasy land. There’s precedence for this: Some old maps look cool but really aren’t that accurate. Ancient maps were often created by people who hadn’t been to the places they were depicting. They didn’t know the distances between Alexandria and Constantinople, but they might know from sailors that there were this many cities between the two destinations. So, they’d just equally space out the ports between the two cities on the map. It didn’t mean that there was an equal distance between the ports, but as a sailor, at least you knew which port to look for next and how many ports there were between places.

So, making the map look cool in a distinct style is on my mind more than clarity, even, but in the end, clarity wins over style, and style most often wins over scale.

As I work through the map, I often refer to real-world geography. I made mistakes as a young cartographer that I wouldn’t have made had I known more about geology and geography, and I’m sure there are mistakes I’m making now because I just haven’t learned better yet. Digging into real maps and into the geographic history of real places helps me see where I’m deficient in my skills. You don’t have to know all about the geology of your own made-up world before you make maps. Usually you just place a mountain range where it looks cool and then later on figure out reasons for that range to be there, but it doesn’t hurt to know, for example, where mountains are most likely to appear on a landmass. You can also look at Hadley cells to figure out where to place deserts and trade winds and westerlies to decide on macro wind patterns, desert locations, and general weather and biomes. You can even figure in things like El Niño and La Niña. But don’t get bogged down in the details.

When I get stuck, or I’m browsing for map reference, there are a few places I like to go. I lurk sometimes on a website called cartographersguild.com and glean tricks and tips from the cartographers there who are making some of the coolest maps I’ve ever seen. I’m often combing DeviantArt and artist’s blogs and looking at how they create their lines or color their pieces. I’m most often looking to mapmakers from all over the world in all time periods and seeing what they did. I recently visited a private map collection and talked to the curator about the types of paper and inks that were used on specific maps. That single visit continues to blow my mind and change the way I go about creating maps that look like they came from real historical periods.

Oftentimes new fantasy cartographers will approach me and ask how to get started. Here are a few ideas.

Learn as much as you can about cartography, geology, and geography, but don’t let your research get in the way of actually creating your own maps. The process of creation is where you’re going to run into the problems whose answers (when you discover them) will make you a better mapmaker.

I presented at a convention a few years ago about the seven deadly sins of fantasy cartography. I’m sure there are more than just the seven, but the list is a good place to start when figuring out what not to do on your own maps.

One caveat on this list: Sometimes an author will ask you create the map a certain way, despite these mistakes. I’ve got several maps out there with the same mistakes I’m about to outline. Sometimes the author asked me to keep things that way, other times I’ve made the mistake all on my own. The point here is this: Even if you make the mistake, it’s not the end of the world. You can always retcon the mistake by saying something like, «But the in-world cartographer who made that map didn’t know there was a river there!

The Seven Deadly Sins of Fantasy Cartography

- A map without a purpose. Who created this map? Who commissioned it? Why? This could be as simple as: «I’m a fantasy writer and need to know where everything is so I can write my stinking book. You can break some of the rules if it serves the purpose of the map.

- The scale is unintentionally off.

- Mountains or landforms that don’t follow natural laws. For example, a landmass that looks too perfectly like a dragon–I’ve done that before!–or a range of mountains that are a perfect line north to south (unless this is the intentional style of the map), but mountains don’t normally form naturally in perfectly straight lines.

- Rivers that flow uphill.

- Climates and biomes placed where they likely wouldn’t form in reality. (Along with this are the planets that are all one biome. George Lucas got away with this one, but that doesn’t mean it’s true-to-life.)

- Placing towns and cities where they don’t make logical sense. (Ie. Nowhere near a fresh source of water.)

- Borders that aren’t consistent with their time period. National borders that are straight lines are relatively new. Look at something like the borders of states in the Holy Roman Empire. They look like puzzle pieces.

C: Hablemos un poco sobre cómo acaba un cartógrafo de mundos fantásticos como Director de Arte de Dragonsteel. Porque, algunos lectores pueden desconocer este dato, pero estás realmente involucrado en el proceso creativo de los libros. Tiene que ser muy emocionante ver cómo crece este proyecto. ¿Cuándo empezaste a trabajar con Brandon?

IS: Cuando trabajaba para la empresa de software y vídeos educativos, empecé a preguntarme qué había hecho con mi vida. Hacía tan solo unos años que había salido de la facultad, y estaba disfrutando de mi trabajo, pero no del desplazamiento. Había visto pasar a la compañía por varios despidos y por enviar trabajos al extranjero. ¿Qué tan sostenible era el trabajo? ¿Quería seguir haciendo eso el resto de mi vida? Trabajé con personas talentosas (mucho más talentosas que yo), gente por la que llegué a preocuparme, y cuyo trabajo tenía en gran estima. Pero necesitaba encontrarme a mí mismo.

Así que decidí volver a la universidad para otro grado. Esta vez, optometría.

Durante el segundo semestre en la facultad, quería volver a tomar las clases de escritura de fantasía y ciencia ficción de nuevo. En mi época universitaria, eran impartidas por David Farland, y había asistido dos veces. Ahora las impartía Brandon Sanderson, quien tenía una novela a punto de ser publicada al año siguiente. Me preguntaba si este tal Sanderson podía escribir, así que me di el capricho y busqué su nombre en el sistema informático de la biblioteca universitaria y encontré su tesis, un libro llamado Dragonsteel. Fui la primera persona en echarle un vistazo. Devoré el libro, y me di cuenta de que, desde luego, este tal Sanderson podía escribir. Tomé sus clases, donde nos dimos cuenta de que nuestras edades acercaban mucho más que las demás personas allí. Nos hicimos amigos. Una noche, después de clase, fuimos a Macaroni Grill, donde te dejan colorear con ceras sobre los manteles de papel. Me vio garabatear y preguntó si me gustaría hacer el mapa para su siguiente libro, Nacidos de la Bruma.

Había estado garabateando durante mucho tiempo. En los márgenes de mis apuntes en las clases de ciencias, en mis agendas cuando fui misionero en Filipinas, en libros de bocetos, etc. Jamás me imaginé que dibujar por aquí y por allí fuera a proporcionarme un trabajo.

Después de aquel semestre, hice trabajos raros de diseño, trabajé en un hotel como recepcionista nocturno, y eventualmente me enrolé de nuevo como artista 3D y animador en compañías de vídeo juegos. Trabajé como freelance para Brandon entre 2005 y 2013, momento en el que nos contrató a mi mujer Kara y a mí para trabajar para él a tiempo completo. La optometría no dio resultados, pero garabatear sí.

C: Y esto es todo por esta semana. Esperamos que hayáis disfrutado de la lectura, de conocer un poco mejor a Isaac y su trabajo como cartógrafo, y de sus consejos sobre la creación de mapas para mundos de fantasía. La semana que viene hablaremos sobre su faceta como director de arte para Dragonsteel Entertainment, y muchos temas relacionados con los libros de Brandon. ¡Os esperamos!

C: Let’s talk a bit about how a fantasy cartographer ends working as Dragonsteel’s Art Director. Because, some readers may not know, but you are really involved in the creative process of the books. It must be really exciting to see how this project grows. When did you started to work with Brandon?

IS: When I was working for the educational software/video company, I started to wonder what I’d done with my life. I was only a few years out of college, and I was enjoying my job but not enjoying my commute. I’d seen the company go through a few layoffs and send some jobs out of the country. How sustainable was the job? Did I want to do that my whole life? I worked with talented people–way more talented than myself–people I’d come to care for and whose work I held in very high esteem. But I needed to find myself.

So I went back to school for another degree. This time for optometry.

I know, you’re probably thinking “Wut?” Maybe I should’ve been thinking that too. But I already had most of the prerequisite classes for dental school, and I figured if I was going to be doing a job that wasn’t really fulfilling to me, I might as well be making a lot of money doing it. So I went back to school.

Second semester back at school, I wanted to take the science fiction and fantasy writing class again. It had been taught by David Farland back during my undergrad days, and I had taken it twice. I looked it up. It was now taught by Brandon Sanderson, who had a novel coming out that next year. I wondered if this Sanderson fellow could write, so on a whim I typed his name into the university library computer system and found his honors thesis, a book called Dragonsteel. I was the first person to check it out. I devoured the book, and realized, indeed, that this Sanderson guy could write. I took his class, where we realized we were closer in age than most everyone else there. We became friends. One night after class, we went to Macaroni Grill, where they let you color with crayons on paper tablecloths. He saw me doodling and asked if I’d like to do the map for his next book, Mistborn.

I’d been doodling for a very long time. In the margins of notes in science classes, on my daily planners when I was a missionary in the Philippines, in sketchbooks, etc. I never expected that doodling here and there would ever get me a job.

After that semester, I did odd design jobs, worked at a hotel as a night clerk, and eventually wound up again as a 3D artist and animator at video game companies. I did freelance work for Brandon on the side from 2005 to 2013, when he hired both me and my wife Kara to work for him full time. Optometry didn’t pan out, but doodling did.

C: And that’s all for this week. We hope you enjoyed the read, and getting to know Isaac a bit more as well as his works as a fantasy cartographer, and his hints and tips on creating fantasy maps. Next week we will be talking further about his Art Director at Dragonsteel Entertainment side, and other topics related to Brandon’s books. Looking forward to see you back!

Tamara Eléa Tonetti Buono

Apasionada de los comics, amante de los libros de fantasía y ciencia ficción. En sus ratos libres ve series, juega a juegos de mesa, al LoL o algún que otro MMO. Incansable planificadora, editora, traductora, y redactora.

Post a Comment

Lo siento, debes estar conectado para publicar un comentario.